For the past two years, John Brooks has asked dozens of friends and acquaintances, but also total strangers, to sit for him while he makes their photograph. These sessions have taken place in Andros, Aspen, Athens, Miami Beach, New York, Southampton, and beyond. Occasionally, when time or distance does not allow, he will instruct the sitter on how to position and photograph themselves, all in preparation for the single drawing he will make of them at his studio in the Portland neighborhood of Louisville, Kentucky. The only common thread among his subjects is a distinct point of connection—something as banal as an Instagram like or as profound as shared history.

Brooks—artist, poet, and curator—is an active member of Louisville’s creative community but has largely relied on social media and long-distance communication for inspiration. Friendly DMs have grown into ongoing dialogues, enabled by what Brooks calls “the whims of the algorithm.” Beiruti is the result of one such conversation, born from a friendship forged on Instagram through discussions of architecture, politics, and queerness. In the cases where Brooks meets his online subjects in person, they are already familiars, the connection equally and often more powerful than physical nearness. This concept is reinforced in A Skippidy Doo Da Day (2002), a portrait of Brooks’ late grandfather that records a true connection despite the subject’s absence. Through Brooks’ hand, the virtual and physical are inseparable, reconciled in a realm where distant connections, local landscapes, and wistful memories may coexist.

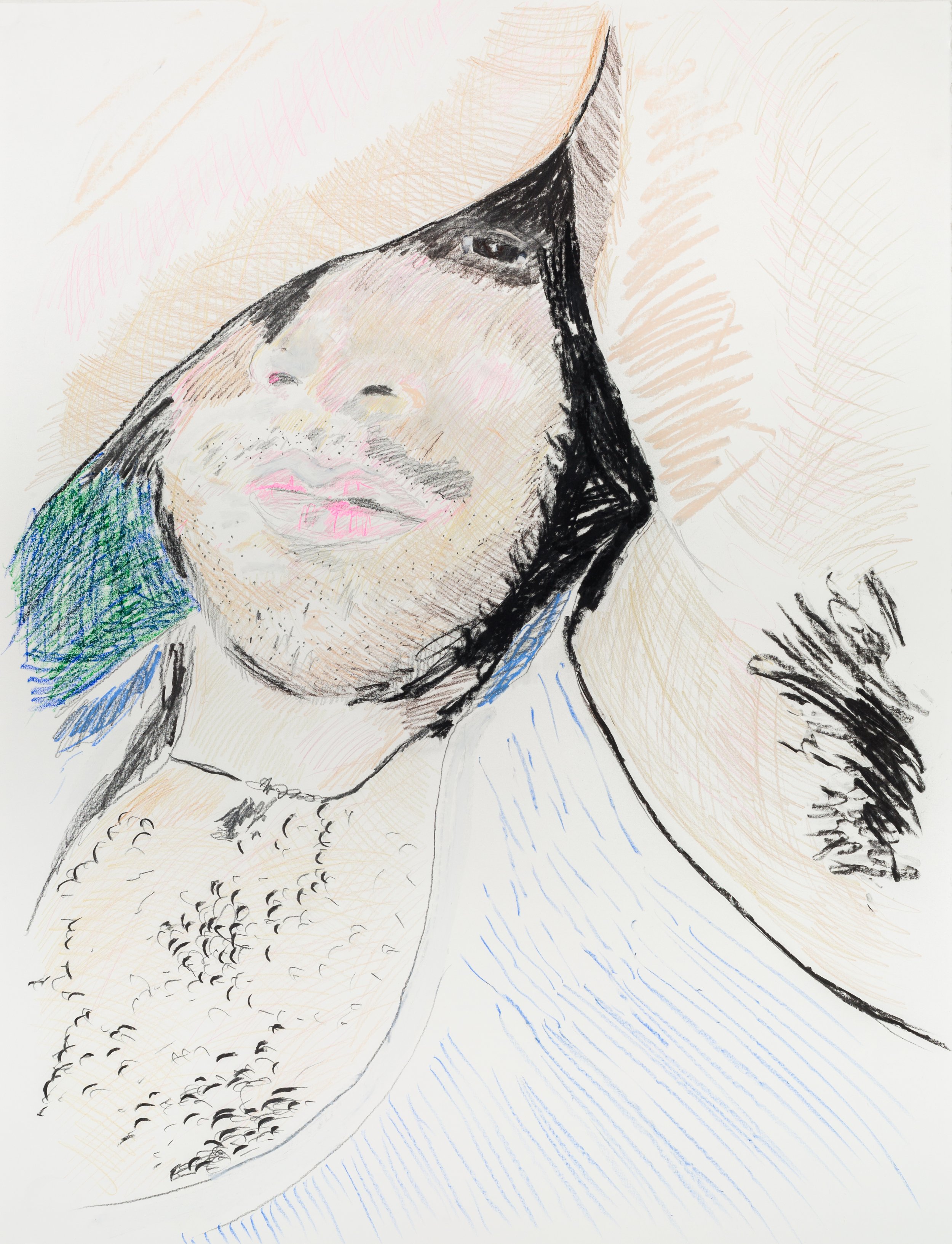

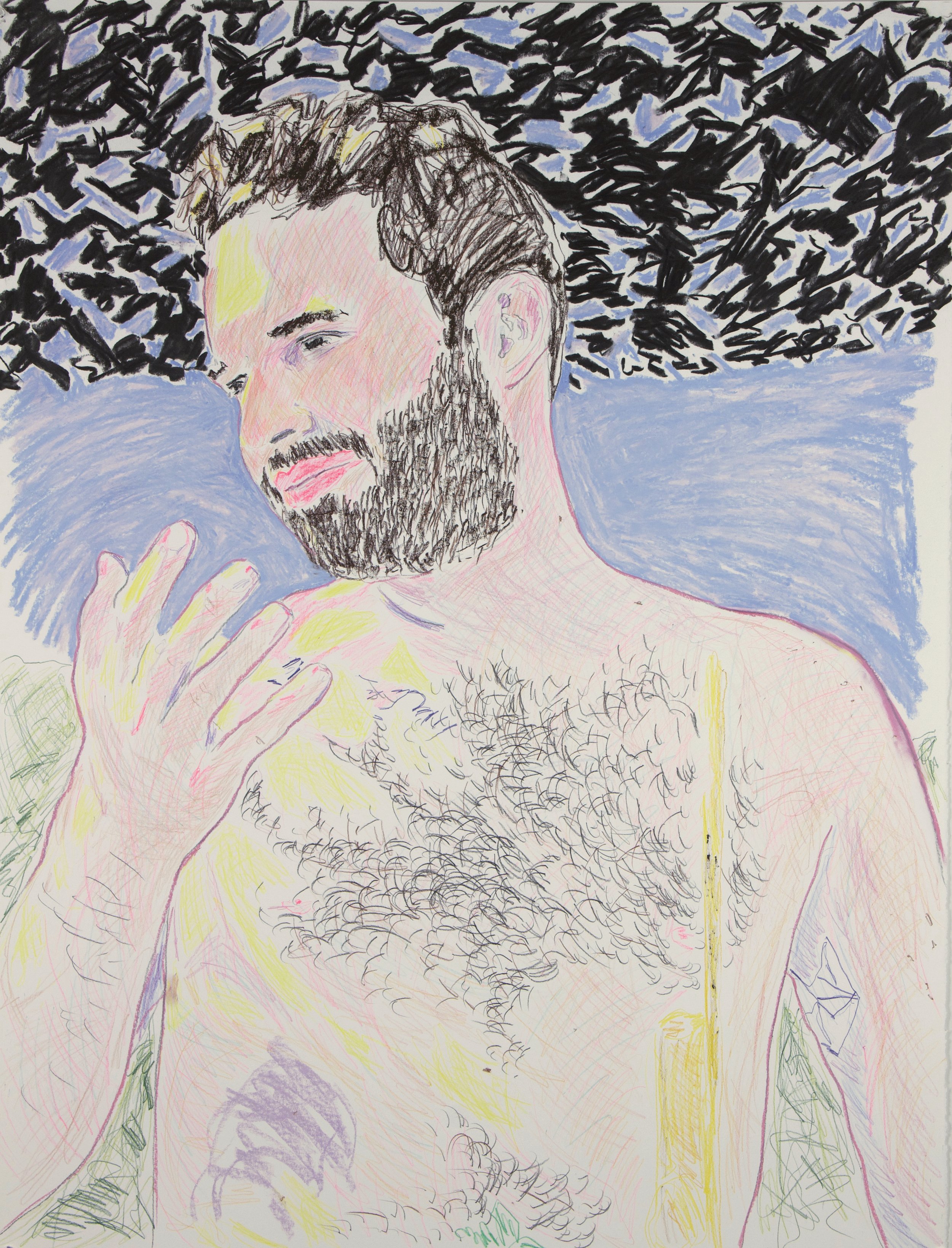

Brooks’ studio is full of these mostly larger-than-life portraits, an imagined community created by an artist at home in solitude yet fascinated by connection. Within each work lies layers of shared experience; the indulgent or humorous is reconciled with the profound. They are collaborative, a combination of what is offered and what is recorded, requiring the artist’s willingness to surrender his hand to the experience of others and the subject’s desire to express themselves truthfully and entirely. Brooks approaches this process with great reverence, distilling personal histories, pleasure, loss, and desire into oversized frames.

The scale of the drawings is both joyful and unsettling, ultimately allowing for a deeper immersion in the artist’s world. Far larger than any smartphone or computer screen, these are not images to peer into, but to meet head-on. Similarly, their creation demands the artist’s entire presence, the mark-making alluding to full-body gestures and constant motion. Brooks’ marks swell and break like waves or music, dense yet easeful. The gentle palette affirms an underlying nostalgia, one powered by the longing that inspired such scenes. Brooks’ connections float upon the page, preserved in a realm separate from our own, where connection transcends time and space.

John Brooks was born in central Kentucky in 1978. He studied Political Science and English Literature at the College of Charleston, South Carolina, with continuing education in art at Central St. Martins and the Hampstead School of Art in London, England. His work has been exhibited across the United States and Europe, and is included in the collections of the 21C Museum Hotels, Grinnell College Museum of Art, among others. Most recently, Garth Greenwell penned a feature article about Brooks for the The New Yorker titled “A Kentucky Painter’s Travels in Queer Time.”

A Man Lost in Time Near KaDeWe

La Ritournelle

Beiruti

Night in Despair

Time to Float

A Skippidy Doo Da Day

Of course there is nothing the matter with the stars / it is my emptiness among them / While they drift farther away in the invisible morning - WS Merwin

The Ghost in You

Before I Caught Your Coldness

Mother Will Never Understand Why You Had to Leave

She's Got Everything She Needs, She's an Artist, She Don't Look Back

A cuckoo sings / to me, to the mountain / to me, to the mountain - Kobayashi Issa

A clear moon / because of his fear of foxes, / I go with my lover boy - Matsuo Bashō

I Used to be Free, I Used to be Seventeen

Makes Me Wish I Was Empty

Ammunition

Live This Day

We Two Boys Together Clinging