The World in the Evening

Moremen Gallery

September 1 - October 7, 2023

710 West Main Street, Suite 201

Louisville, KY 40204

Moremen Gallery is pleased to present The World in the Evening, a solo exhibition of new paintings by John Brooks. These works on canvas, all created in 2022 and 2023 and organized in close collaboration with the artist, will be on view from September 1 to October 7, 2023. This marks Brooks’ third exhibition with the gallery, following 2019’s A Map of Scents and 2021’s We All Come and Go Unknown, which was profiled by Garth Greenwell in The New Yorker.

The exhibition’s title is borrowed from the 1954 novel of the same name by Christopher Isherwood, a writer who is often regarded as one of the preeminent chroniclers of the last days of Weimar Berlin, that fertile and decadent home to artists and intellectuals as well as homosexuals due to its liberal views. All that came to an end, of course, with the rise of Nazism and Hitler’s ascent to power in 1933. And indeed, the evocative and unsettling new paintings presented in this show seem to collectively evoke not only Weimar’s violent demise, but also the current post-pandemic world, in which many long held systems and institutions seem to be in their metaphorical twilight.

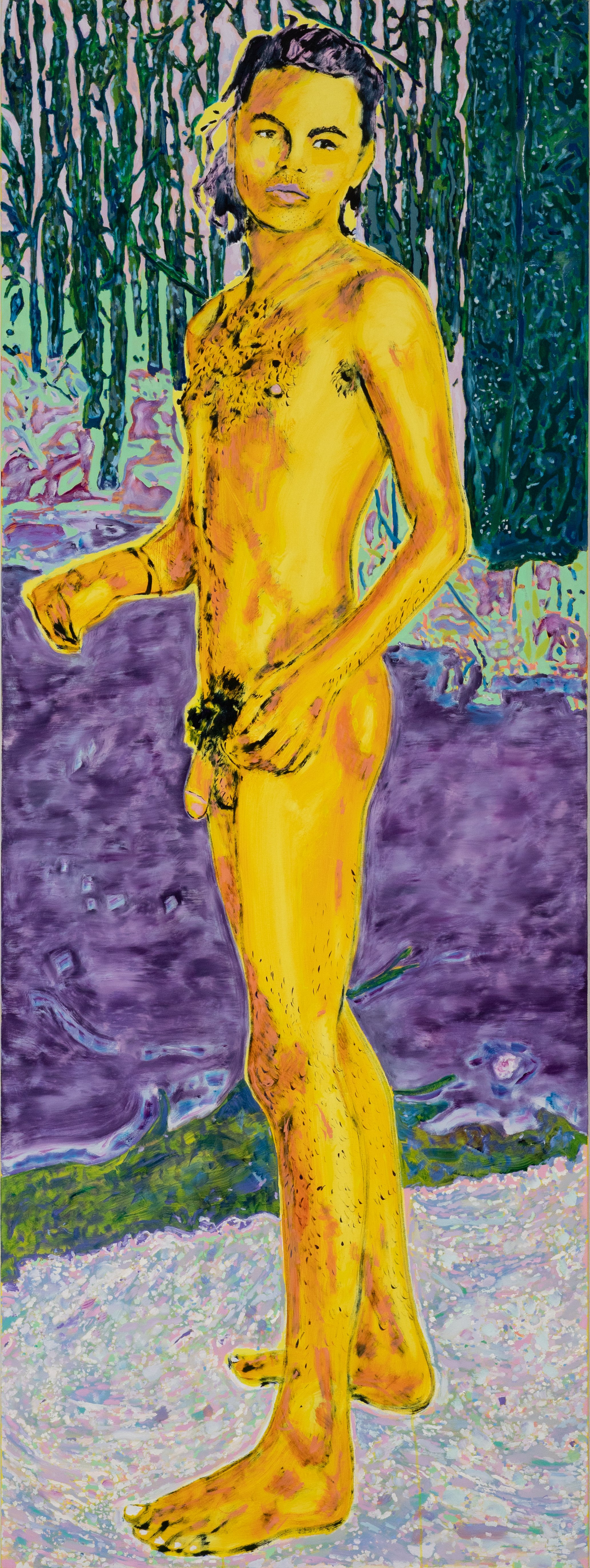

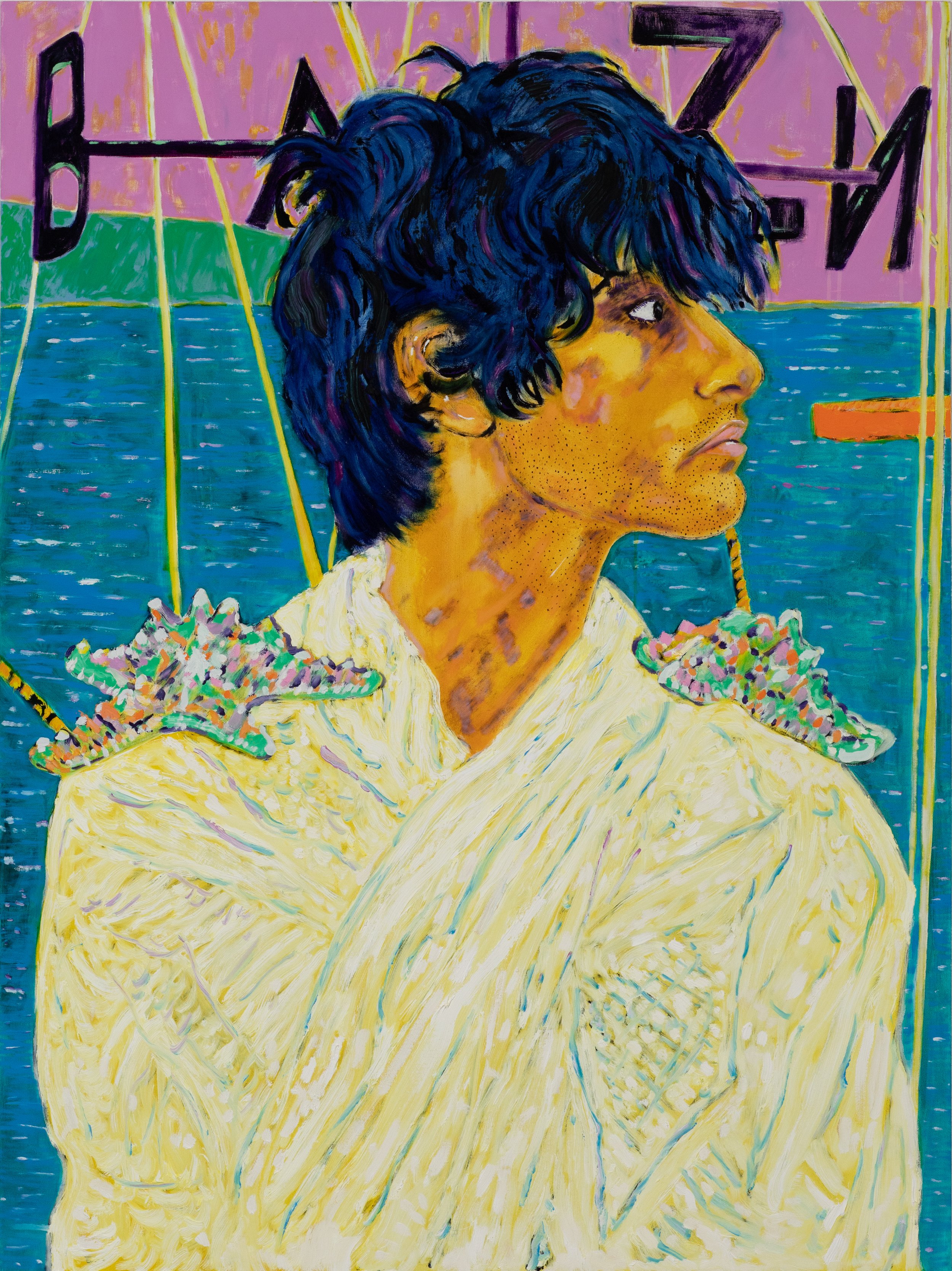

In these works, Brooks pushes his characteristically distinct color choices (a reflection, perhaps, of the artist’s sustained interest in German Expressionism) in strange new directions, amplifying the surreal quality of the compositions and characters: naked men and deer wander in woods dense with violet trees and turquoise vegetation; human skin is often several shades of canary yellow and sometimes magenta; a background might be a jarring juxtaposition of crimson red or deep kelly green. Brooks’ growing formal concerns are also evident in the visceral layers of oil paint that drip, smear, and pile up, as well as the detailed pattern work he increasingly applies to fabrics (garments, curtains) and architectural design elements (wallpaper, carpets and floors).

To speak of a painting’s “characters” seems more appropriate than “figures,” as Brooks is not painting from life but rather composing scenes of people from disparate films, novels, schools of art and historical eras, along with elements of contemporary and historical Queer and pop culture, all commingling with Brooks’ own friends and the artist himself. Evocative titles, most of them borrowed lines from treasured poems or songs, heighten the novelistic quality of the paintings, alluding to storylines that are suggested by the compositions but remain at least partially, stubbornly hidden from the viewer.

The show’s paintings feature such diverse characters as a French reliquary allegedly housing the skull of Mary Magdalene; Jackie Kennedy in mourning; the infamous meeting of Richard Nixon and Elvis Presley; from television’s “What’s My Line,” a masked Dorothy Killgallen, the journalist whose public suspicions over the facts presented by The Warren Commission cast a curious light on her untimely death; family photographs; self-portraiture; religious imagery inspired by Brooks’ Catholic upbringing; both Mary Shelley’s and Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein; and dancer, singer, ingénue and anti-Nazi spy Josephine Baker.

While Brooks’ practice has always been, in some sense, a cataloging of his own interests, inspirations and obsessions, with this exhibition, themes of history and politics, though still nebulous, have become more prominent, and the scale of the works has become increasingly ambitious. The show’s titular work, a sprawling, riotous painting densely populated by a lexicon of allusions, simultaneously wide-ranging and narrowly self- referential, sprawls over two canvases to include (briefly): Brooks’ bass-fishing great-grandmother; imagery from classic films Bringing Up Baby, The Night of the Hunter, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari; borrowed elements from works by painters Noah Davis, David Hockney, Max Beckmann, and Salman Toor; Ronald Reagan; Muhammad Ali; the flag flying at Fort Sumter when the Confederate Army attacked; and the life mask of George Washington.

Like the other works in the show, “The World in the Evening” exists at the intersection of history, Queer culture, and the artist’s personal life in a way that celebrates the mysteries, melancholies and sheer weirdness of human experience. In these imagined environments, sorrows and misfortunes abound but so also do joy and humor. Time has perhaps never been more out of joint, and yet the paintings succeed in evoking both timelessness and ephemerality: places, people and entire military regimes all fall away, but memories and histories endure through both art and artifact.

As Brooks is also an accomplished poet, it seems fitting that it is T.S. Eliot, in a 1921 essay on metaphysical poems, who provides a clue to understanding these lyrical works:

When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience; the ordinary man's experience is chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. The [reflective poet] falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these two experiences have nothing to do with each other, or with the noise of the typewriter or the smell of cooking; in the mind of the poet these experiences are always forming new wholes.

Brooks is indeed possessed of a poet’s mind, particularly attuned to the chaos and confusion of our current moment and eager to capture all of its disparate experience and amalgamate it into strange and surreal new wholes. At a time when it can feel as if everything is falling apart in a great cacophony of dissolution, Brooks reminds us that even earlier eras’ twilights were eventually followed by new dawns, and moments of beauty somehow always find ways to dazzle and endure.

- Natalie Weis

Also Sprach Zarathustra

Caesar's Bed is Double-Warm

Oh No. The Drift of the World

A Thousand Violet Nights

Also This is Lonesome Country

Take This Longing

I Have Spoken With People Who Study Thunder

The Reeds Sigh as the Young God Rises

The Wild and the Gentle Dogs Kenneled in Me

The Moon Stood Still for the Night Bird Song

Tell Me if the Lovers are Losers

Yes, We Had Gone to the Sea Together

These Fragments I Have Shored Against My Ruins

A Thousand Rattlers in the Underbrush

All the Poetry Between the Good and Badness

Things that He Brings that He Found in the Sea

The World in the Evening